New York (Pizza) City

It’s no debate. Pizza rules the New York cityscape like no other food. Stand at any Manhattan corner and look around. Chances are you’ll see pizza. In the outer boroughs — places where people often have cars — density is a bit lower, but still: pizza.

And it’s not just magnitude. The pizza you find is nearly always decent. Even the 99¢ spots that have riddled Manhattan with snaking lines during the past few years of "economic downturn" produce edible specimens. Of course, side by side with a slice of quality pizza, a 99-cent jobbie does not compare (doughy crust and cheap cheese: no thanks!), but for a buck who would complain?

It wasn't always this way. Pizza first arrived in New York (and the US) sometime around 1900. The earliest US pizza shop on record (Lombardi's) began as a small grocery whose owner (Gennaro Lombardi) topped scraps of dough (he was a baker by trade) with tomatoes and/or cheese. For a couple decades, one could find pizza only in Italian neighborhoods.

In the 1930 eating guide "Dining in New York," intrepid food writer Rian James described the pizza at Moneta's (an Italian restaurant on Mulberry Street) as "an inch-thick potato pan-cake, sprinkled with Parmesan Cheese and stewed tomatoes." Yuck!

On September 20, 1944, the New York Times's triple-row front page headline read

BRITISH NEAR RHINE IN 37-MILE SWEEP NORTH AFTER AIR ARMY JOINS IN CAPTURING EINDHOVEN; RUSSIANS 7 MILES FROM RIGA IN BALTIC PUSH.

and buried on page 19 amongst mainly stories of the war was a piece entitled "News of Food: Pizza, a Pie Popular in Southern Italy is Offered Here for Home Consumption." In it, food writer Margot Murphy (aka Jane Holt) offered a thorough and enticing description of pizza:

One of the most popular dishes in southern Italy, especially in the vicinity of Naples, is pizza - a pie made from a yeast dough and filled with any number of different centers, each containing tomatoes. Cheese, mushrooms, anchovies, capers, onions, and so on may be used. At 147 West Forty-eighth Street, a restaurant called Lugino's Pizzeria Alla Napoletana prepares authentic pizze, which may be ordered to take home. They are packed, piping hot, in special boxes for that purpose.

Pizza had expanded beyond Little Italy to Midtown!

I romanticize New York's past, especially when it comes to steam rising from manholes, crisp metal skyscrapers, the endless shuffle of all kinds of people, and (of course) neon pizza signs outlined by flashing yellow bulbs. But as fast as New Yorkers may hustle down sidewalks today, I imagine an even brisker pace in 1944 — fedoras and all. Murphy wrote that "after five to seven minutes of baking (the oven is kept at an extraordinarily high temperature) it is ready to serve, the whole operation having taken not more than ten or twelve minutes." Two pies to go, please!

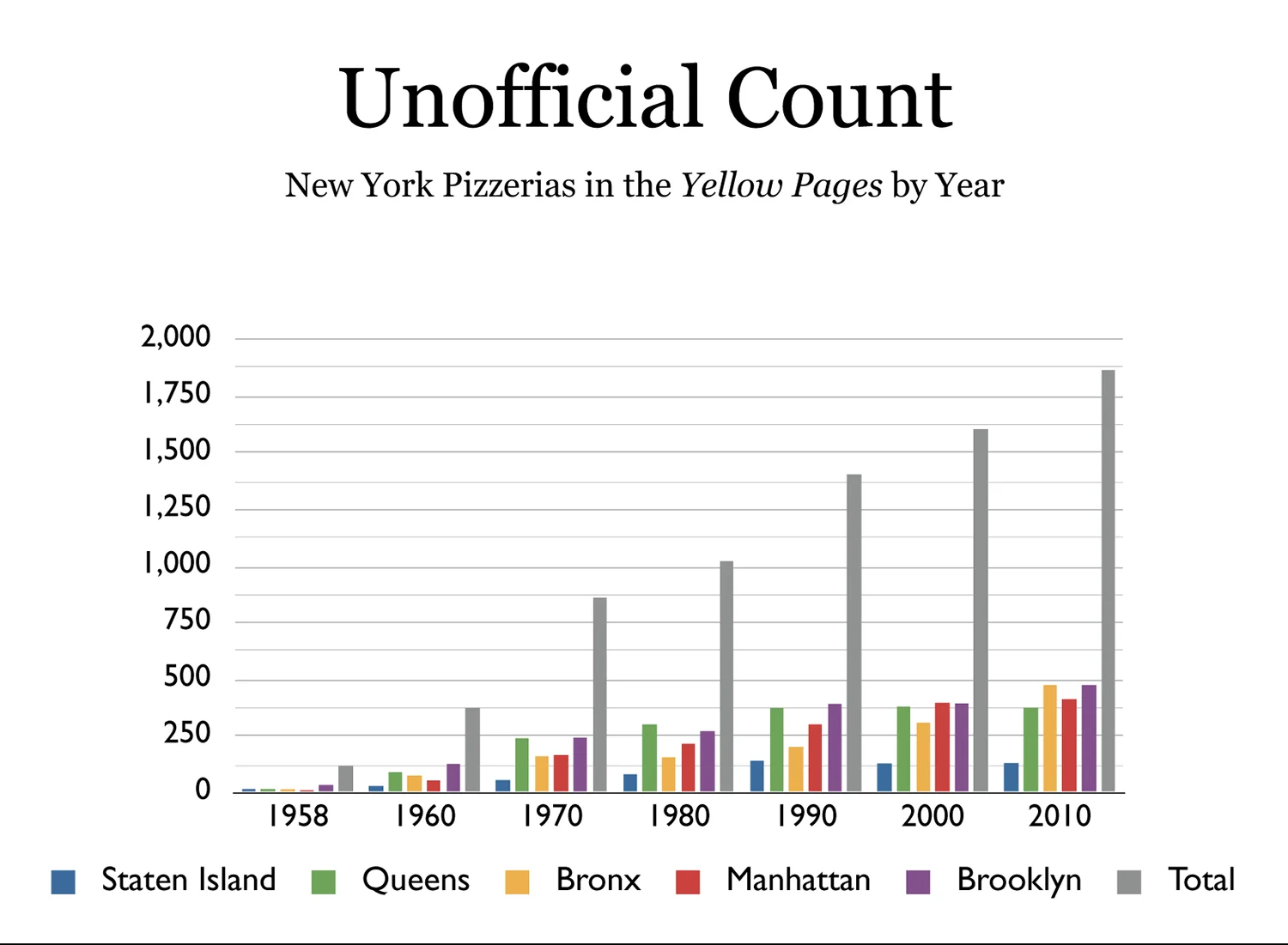

I spent some quality time in the microfilm room at the New York Public Library, thumbing page by page through old phone books. "Pizza" as a separate category first appeared in 1958, but has never included certain full-fledged restaurants that happen to serve pizza. (Lombardi’s, over the years, appeared under "Restaurants - Italian," but not under the “Pizza” heading.)

The count is not definitive, but the results are telling: the greatest decade-over-decade citywide increase came between 1960-1970 (+231%). Factoring in the two years of available data prior to 1960, the 1958-1970 increase was 735%. Wow! (Click on the graph at the top of this piece for raw data, &/or scroll to bottom for count methodology.)

A number of factors contributed to pizza’s incredible ascent: celebrity enthusiasm, Americans' increasing curiosity in and willingness to try different ethnic foods, and a national trend toward convenience (eg. TV dinners, fast food). But none had as much of an effect as did changes in pizza oven technology.

Leading the charge was Frank Mastro, a restaurant equipment shop owner who tinkered with ovens, converted them to gas, and together with a thermostat company developed the gas deck oven (the oven used by most pizzerias).

Gas made pizza-making much easier. A craft that was limited to bakers skilled in working very hot, huge, and finicky coal ovens became a career for people without baking or pizza skills. Instead of stoking coal, pizzaioli now had only to turn a dial.

In 1957 a Saturday Evening Post article entitled “Crazy About Pizza" asserted that Frank Mastro had “done [the] most to popularize pizza.” It described a “model pizzeria [he had] in his store to show prospective pizzeria owners how to run their operations." According to his daughter, Madeline Mastro Ferrentino, Mastro also financed oven purchases from out of his own pocket. The dude believed in pie.

Fast forward to today, through decades of continued growth for pizza — more Italian immigrants, Greek-owned shops, the thick-crust Chicago-like craze, haute and pricey pizza, and the more recent surge in "new Neapolitan" restaurants (pristine ingredients, wood fired ovens, single-plate pies, and accomplished chefs as owners) — and yet the endless array of slice joints still dominates. Thank heavens — who doesn't love a meal for under $10?

The other day, I spent a little time during lunch hour at My Little Pizzeria — a good place located in a busy area of downtown Brooklyn, close to city courts and a number of office buildings. I was there to document the preparation of their amazing "Supreme" pie for a future piece. For a while, I zenned out on the long line and how the staff of five churned out pizza with such flair and efficiency. And this sort of thing is going on all across the city, every day: people making pizza, people eating pizza, people loving pizza. By the thousands.

I made a short video of pizza in action. View it by clicking the above photo.

--

Notes on the counting method:

I went page by page through Yellow Pages books from each of the five boroughs. I counted every pizzeria listed under "Pizza" but avoided double counting any same-named listings at the same address.

On the "Yellow Pages" website, a search for the business type "Pizza" in Brooklyn today yields a list of 1,149 pizzerias — a number far greater than the 475 I counted in the 2010 print Yellow Pages. I cannot explain the discrepancy because I do not know the criteria for listings inclusion with either resource. The website may allow broader criteria (perhaps the keyword "pizza" is enough to merit inclusion); it may not have purged pizzerias that closed two years ago; and may include redundant or non-Brooklyn listings (#114, for instance, is Famous Rays of Greenwich Village in Manhattan). The print Yellow Pages might be missing listings — I imagine that today its production is limited to a small staff — and in years prior, it's possible that many pizzerias were omitted. Therefore, I've called the results of my count "unofficial."

The only way to tally pizzerias in the past is to use the print Yellow Pages. If, over the deades, the Yellow Pages employed an even methodology to the compiliation of its listings, then the proportionate growth in the number of pizzerias should be statistically accurate.