The Freedom of Pizza

Photos by Scott Wiener, 2017

1. Me

Pizza inspires passion. Whether it’s a debate about which city has the best pizza or which neighborhood pizzeria serves up the superior slice, everywhere you go, opinions about pizza are legion, arguments are fierce, loyalties are lifelong — and everyone is an expert.

I witnessed that passion at my Uncle Charles’s restaurant. In 1977, he opened Geppetto on M Street on the edge of Georgetown in Washington, DC. His pizzas quickly became legendary, and not long after, so did the waits. Geppetto maintained a no-reservation policy, and with no bar area, patrons had to wait outside on the street when the 60-seat dining room was full. And whatever the weather, wait they did — sometimes for as long as two hours. It didn’t matter whether you were a tourist or a native Washingtonian; whether you were a rock band on tour (Van Halen waited), news anchor (Charlie Rose waited), or politician (a young Senator Joe Biden and his family waited). During one brutal evening, a manager reported that the King of Jordan was among the throngs hoping to get a table. Uncle Charles looked up from his work and with just a hint of a smile replied, “At Geppetto, even royalty waits.”

I still laugh when I recall composer Marvin Hamlisch’s unrelenting obsession. In town frequently for shows at Constitution Hall or the Kennedy Center, he was often booked on local radio and TV programs to promote his gigs. But as often as not, he’d veer off topic and rhapsodize about Geppetto — the mounds of pepperoni piled on the Neapolitan pie, or the perfect fontina cheese of the garlicky white pizza. Befuddled reporters tried in vain to steer the interview back to music, but it was a lost cause. Hamlisch was in the throes of pizza delirium and simply couldn’t help himself. (I will admit that Marvin was the one person who never had to wait for a table at Geppetto).

I moved to New York City in 1987 for college and roamed the streets on foot, camera in hand, taking in the neighborhoods and the nuanced changes that occur block by block. I also discovered what New Yorkers

already knew: really, really good pizza is everywhere.

The Stromboli Pizza near my dorm was on University Place near 12th Street. This photo shows the other Stromboli location — at the time equally good and very busy — at Second Avenue and St. Mark’s Place, c.1991.

The go-to joint near my dorm was Stromboli Pizza. It was a bright, mirrored little room that was busy all the time: at night with college kids and tipsy drinkers who’d spilled out of the neighborhood bars; during the day with office and retail workers on lunch break. I ate at the ages-old John’s Pizza on Bleecker Street, where the walls and booths were covered with scratchiti, and it smelled of dark toast and sweet tomatoes. When I visited friends up at Columbia, I went to Koronet on Broadway where a single slice from a gigantic 32” pie provided fuel for the day. One cold night, my girlfriend and I drove to Coney Island — desolate in the winter — where with the help of a friend, we downed three charred pies at the legendary Totonno Pizzeria Napolitano. At Di Fara, where there was no discernible line, I waited and salivated and — mesmerized by the styrofoam coolers of buffalo mozzarella just flown in from Italy — I waited some more.

The 32” pie at Koronet, on Broadway near 111th Street, in 2002.

Over the last dozen years as a photographer I’ve covered everything from club openings to crime scenes, sent on assignment by newspapers to neighborhoods in all corners of the city. These forays also were personal pizza hunts — yondering quests to discover the best pizza wherever a job took me. Though there’s always more “research” to do, I think I’ve compiled a good list. If you name the neighborhood, I’ll name the joint. Canarsie? Original, on Avenue L. East Harlem? Patsy’s. South Beach, Staten Island? Lee’s Tavern.

Perhaps no food is more personal and more intimate. At many pizzerias, the guy behind the slice also owns the business. Check out his hands and forearms — those calluses and scars tell stories: he wrote the recipe long ago and perfected it over the years; he made the dough and sauce that morning or the night before; and he is the one who reaches into that 700-degree oven. If you’re a regular, he knows your name, knows what you like, asks about your kids, and tells you neighborhood tales. It’s not unlike the local tavern: the bar is the counter, your bartender is the pizzaiolo, and instead of beer and booze and lemons and limes, it’s cheese and sauce and oregano and garlic. Pizza is the elixir.

My mission as a pizza documentarian is to explore the dynamic, unique and visual circumstances of pizza culture in New York. To show how a dish that first arrived in this country as a low-cost, largely improvised food for poor immigrants changed not only the eating habits of New Yorkers, but also the culinary landscape of this country. In this era of repetitious chain restaurants and caesar salads, pizza boasts as many variations as the people who make it, and continues to galvanize communities and inspire innovation.

Dom DeMarco grating cheese the old fashioned way at Di Fara, in 2002.

Visually, the impact of New York City pizza goes beyond cheese and tomato pies. At Di Fara, a hand-cranked grater clamped to a floury worktable reflects owner Dom DeMarco’s refusal to speed his process. At Louie and Ernie’s, it’s the table of girls seen through the window out back — their sweatpants, long fingernails, low voices, and eye contact all about boyfriend gossip. Balls of cloud white mozzarella neatly stacked atop the candle lit marble counter at Lucali highlight proprietor Mark Iacono’s calm demeanor as he assembles pies and manages his restaurant — both at the same time. The piano and drum set, even when unmanned, take us back to the Village circa 1960s, where jazz clubs may have lined every block but even then, Arturo’s was the grooviest spot in town for coal oven pizza. And of course it’s any one of the thousands of single room pizzerias in the five boroughs where people crowd a worn Formica counter and wait to ask the same question: “Can I get a slice?"

***************

2. New York’s First Pizza

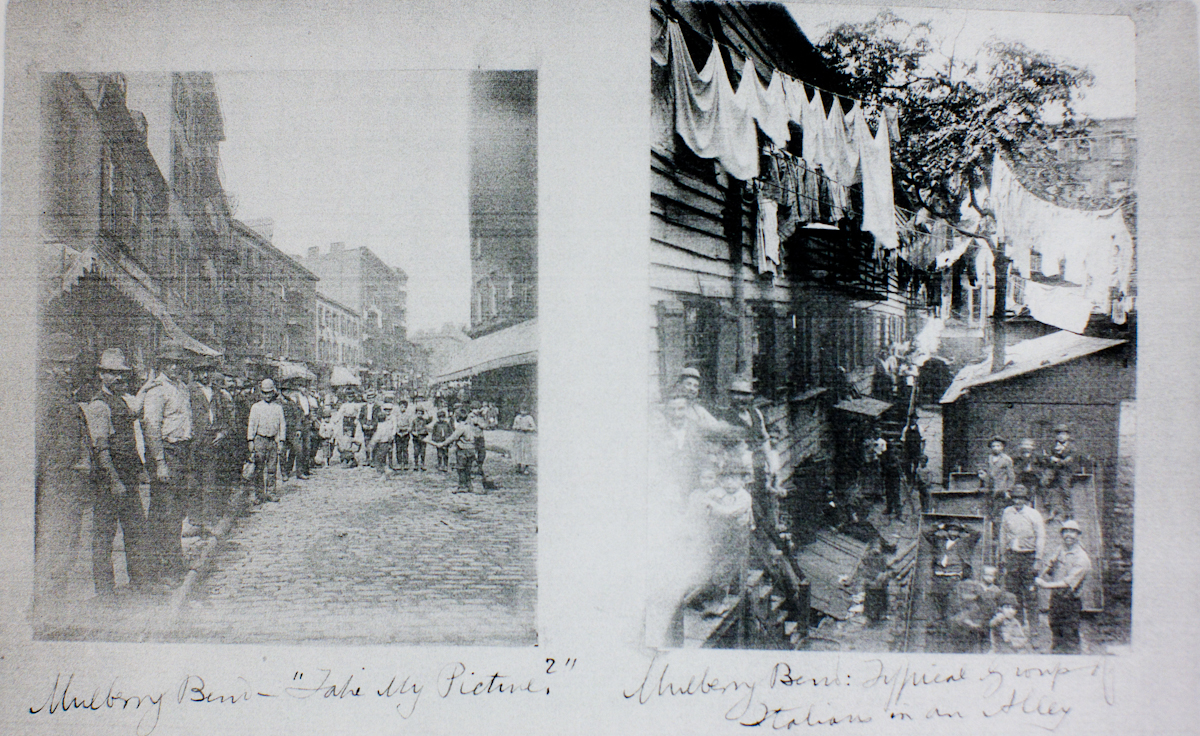

Photographs of Little Italy ― then known as "Mulberry Bend" ― c. 1900.

Reproduced courtesy of the Brooklyn Public Library ― The Brooklyn Collection.

Between 1880 and 1930, more than four million Italians came to the United States. In New York, many lived in tenements and worked in factories. They were downtown in Little Italy; uptown in East Harlem; in Bensonhurst, Carroll Gardens, and Williamsburg, Brooklyn; South Beach and Rose Bank, Staten Island; and Arthur Avenue in the Bronx. Exactly when and where pizza arrived has long been the subject of debate, but one cannot overstate the influence of Gennaro Lombardi. His legacy looms large, even today, over the New York — indeed, the American — pizza landscape.

In the 1890s, Lombardi, a young Italian trained as a baker, immigrated to New York from Naples. By day, he worked in a small grocery on Spring Street; at night, he baked enormous breads in a timeshare oven in Brooklyn — afterwards transporting his loaves by horse and wagon to Little Italy (then known as Mulberry Bend). He sold some of his wares to the grocery, and the rest he peddled on the street, shouting, “O pane! O pane!” (Italian for “Bread! Bread!”). When Italians called down to him from their tenement windows, he hustled up the stairs and delivered right to their apartment doors — no extra charge.

Because most of the Italians were poor, Lombardi and the grocery tailored their wares to fit tight budgets. The store portioned its products as necessary, selling single plum tomatoes from the can à la carte, and Lombardi began to sell sparsely-topped scraps of dough, baked in various sizes. He made these pizzas thin — like the ones he’d eaten in Naples — and wrapped each in paper, using string to tie several together in stacks for the trip back to Manhattan.

Many Italians worked in Soho textile factories that had windows spanning from floor to ceiling. Those who bought pizza from Lombardi ate half for breakfast and saved the rest for lunch — keeping it warm in the window sills.

When, in the early 1900s, the grocery owner decided to return to Italy, Lombardi bought the building along with the store, and promised to send checks to the owner’s family for the next twenty years. He also installed a huge coal-burning baker’s oven in the back of the shop.

Anthony “Totonno” Pero (l) and Gennaro Lombardi (r), c.1905.

We’ll never know who was the very first person to sell pizza in New York City. However, writings on the topic — such as Ed Levine’s anthology “Pizza -- A Slice of Heaven,” — credit Lombardi: “Lombardi acquired his official business license to open and operate the first pizzeria in New York City at 53½ Spring Street in 1905.” A photograph of Lombardi and Anthony “Totonno” Pero — who went on to open his own pizzeria — shows them standing in front of Lombardi’s store (the writing on the window says “pizzeria”) and is dated 1905. A 1956 article in The New York Times Magazine stated that “nobody... disputed his claim to having the oldest pizzeria in the United States.”

In the original Lombardi’s, c.1925 (l-r, starting with tall man): Giovanni Lombardi, Filomena Lombardi, Gennaro Lombardi (back row), and George Lombardi (other two men to the right and people in the booth to the left, not unidentified).

I learned from Lombardi’s grandson Gennaro “Gerry” Lombardi, that Lombardi (the senior) continued to run the business as a grocery that also sold bread and pizza until around 1920, when he converted it to a full-fledged Italian restaurant and pizzeria. At this point he began to make his pizzas much bigger. Customers often dined with their families, and Lombardi’s larger 18” pies — cut into eight slices — could feed four people.

For decades, Lombardi’s was an important hub of Little Italy. During the day, it served the local community — families, workers, and the elderly — and at night, it remained open until the wee hours, attracting a more affluent crowd that influenced celebrities like Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso in the early years, and Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby in the 1950s.

During renovations of the original Lombardi’s in the 1930s, Gennaro’s wife Filomena

sat outside the restaurant to inform passersby that Lombardi’s was still open for business.

Gennaro Lombardi was also the de facto patriarch of American pizza — in fact, people knew him as Don Gennaro. He sponsored innumerable Italian immigrants — many bakers like himself. He provided them with room and board, and jobs as bakers. Anthony “Totonno” Pero and John Sasso each immigrated to New York under Lombardi’s sponsorship, and each saved enough to open his own place — Pero with Totonno’s in 1924, and Sasso with John’s Pizza (originally called Pizzeria Port’Alba) in 1925.

During the first half of the 20th century, pizza helped to sustain some of New York’s earliest shops, but their clientele still comprised mainly Italian immigrants and their children. Pies were not flying out the door and most Americans hadn’t yet heard of pizza. But this was about to change.

***************

3. The 1950s - 1980s

Mastro's ad for a gas-burning pizza oven ran in an Italian-language newspaper in New York, mid-20th cenutry.

By the 1950s, a curious thing happened: pizza gained mass appeal. Some histories cite American soldiers who discovered the food while serving in Italy during World War II as the reason for its success. I like to imagine the headline: WAR ENDS, AMERICANS DEFEAT ITALIAN FASCISTS AND CLAIM PIZZA AS OWN.

As demand increased, more shops opened. But the original coal-burning pizza ovens were huge, expensive, and temperamental — and only skilled and watchful pizza men could work them. Frank Mastro, owner of a large restaurant supply shop on the Bowery, addressed this problem and enabled generations to bake pizza more easily. He tinkered with ovens, converted them from coal to gas, and developed the prototypical gas deck oven. The 1957 Saturday Evening Post article “Crazy About Pizza,” credited Mastro with “having done most to popularize pizza,” and described the “model pizzeria [he had] in his store to show prospective pizzeria owners how to run their operations” as integral to Mastro’s business strategy. It was inexpensive to open a pizzeria and newcomers had a good chance for success — in the 1950s, ovens cost less than $200, the markup on a pie was nearly 300%, and to increase sales, Mastro himself financed many purchases.

Image of an early gas deck oven produced by Frank Mastro.

Not only did gas ovens make pizza more economical to cook, but because they produced evenly cooked crust — without burnt areas — pizza became more palatable to a broader population.

Television and silver screen stars further broadened pizza’s popularity. Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Jackie Gleason, and many others all touted pizza in their shows, movies, songs — and personal lives. Walk into an older pizzeria, and there’s a good chance you’ll find a Frank Sinatra photo or poster on the wall.

Italian immigrants continued to come to New York, and many — over 900 between 1958 and 1980 — opened new pizzerias. Pizza became familiar and ubiquitous in New York City.

***************

4. The 1980s - 2012

By the 1980s, what had been an inexpensive food for immigrants, and then an affordable food for the masses, also became haute cuisine. It began in California in 1981 when Wolfgang Puck opened Spago and served little pizzas with eclectic ingredients on beautiful china to an A-list crowd. Pizza was suddenly gourmet — and the era of (at times) questionable experimentation had begun.

Food writers played along, promoting pizza as a fancy food in their restaurant reviews. In 1985, New York Magazine critic Gael Greene wrote a cover story called “The Joy of Pizza.” She picked Fiorello’s, a pricy place near Lincoln Center, as her favorite. She especially liked their “East Side Juliano” pizza, which was topped with “two runny sunny-side-up eggs and crisp bits of smoky bacon.” In 1987, Times reviewer Bryan Miller wrote that one of his all-time favorite appetizers — “puffy-crusted little pizzas slathered with a piquant wasabi mustard and topped with tuna sashimi” — was on the menu at the Quilted Giraffe, a Midtown restaurant geared toward “the sort of big-league corporate clients that frequent the Four Seasons.” Eggs and raw fish on pizza? What would Don Gennaro Lombardi think?!

Fortunately, creativity wasn’t only for the rich. In 1987, a pair of filmmakers opened Two Boots, a new kind of pizzeria in the East Village on Avenue A. It was colorful and artsy, and drew local punks, artists, and college kids on a budget. The pizza — affordable and unusual — was inspired in part by the popularity of Cajun cuisine. It featured a cornmeal-dusted crust, a cayenne-spiced sauce, and a choice of toppings that included andouille sausage, crawfish, and barbecue shrimp.

After graduating from college, I worked for a year at Two Boots To Go, on Avenue A.

Photo shows my coworker Lucas as he spins a dough, c.1991.

By the 1980s and ‘90s, savvy pizzeria owners began to recognize that New York’s earliest pizzerias were assets that could be built into chains, or — in the case of Lombardi’s — opened again (it had closed in 1986). In 1984, John’s Pizza expanded (by 2010 it had three locations, including one in Times Square that, with seating for 500, may be the largest pizza restaurant in the world). In 1990 Patsy Grimaldi, nephew of Patsy Lancieri — another New York pizza pioneer — opened a pizzeria in Brooklyn, under the Brooklyn Bridge. In 1994, John Brescio and Gerry Lombardi teamed up to reopen Lombardi’s: fresh mozzarella, simple San Marzano tomato sauce, and an old coal-burning baker’s oven that harkened to New York’s early pizza days. Patsy’s and Totonno’s also opened multiple locations.

A publicity photo of Gerry Lombardi (l) and John Brescio (r) in the newly reopened Lombardi’s, c.1994.

In 1998 Times reporter Eric Asimov wrote “New York Pizza, the Real Thing, Makes a Comeback,” in which he declared that New York pizza “is a phrase synonymous with greatness,” and, referring to the new openings, proclaimed that “pizza lovers can rejoice: the true New York pizza is back in town.” It was old style New York pizza asserting itself to the slice joints, to the linen napkin restaurants with their raw fish pizzas, and to the world.

Beginning with La Pizza Fresca in the Gramercy Park area, the mid-1990s also marked the start of another trend: pizza’s return from Italy. Naples-style pizzas have not changed for hundreds of years. The dough is moist and yeasty, and a quick bake in a dome-shaped wood-burning oven renders tiny dots of char along the top and bottom surfaces. The cheese is fresh mozzarella, the tomatoes are San Marzano — grown on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius volcano, near Naples — and the size is individual and pricy. As of 2012, there are dozens of restaurants in New York serving these little pizzas for at least $14 each.

***************

Carey Gordon, a longtime customer at Patsy’s, in East Harlem, digs into a slice of sausage, August 2010.

Today, there are at least a dozen English-language blogs devoted solely to pizza and two competing pizza tours in New York. But besides splashy new openings and hundred-year-old establishments, what makes this food so special?

Pizza knows no constrictions. It’s a $1.00 slice in Midtown or a $19 single serving Margherita at Fiorello’s. It’s coal oven mastery or gas oven simplicity. It’s prepared with house-made mozzarella at Orignal Pizza in Canarsie, Brooklyn, or served with mashed-up basil and garlic at South Brooklyn Pizza in the East Village. It’s straight-up cheese and tomato, or it’s an Indo-Pak pie — with curry powder, jalapeños, and loads of onion and garlic — at Famous Pizza in Elmhurst, Queens. It’s cut into slices or it’s not. It’s upside-down, grandma style, Sicilian, or grilled; some make it with clams, others with anchovies and breadcrumbs; it’s even eaten for breakfast.

Pizza is special not only because of the pizza itself. The social environment created by an ever-present owner — this is also pizza. I love to talk to the owners and the customers, I love to listen in and hear the passions and the trivialities, all bundled into the time it takes to eat a slice or two.

The New York pizza culture I celebrate exists because pizza is about freedom. From its earliest days in New York as a career choice for Italian immigrants, to the present era of diverse options, pizza has always captured the imagination of entrepreneurs and diners alike. It is a food without boundaries, beloved in some form by people of all backgrounds.

But in the United States, pizza began in New York City with Gennaro Lombardi. More on this topic here.

***************

Notes:

1. In the writing of this piece I benefited greatly from the editing prowess and sharp memory of my friend and longtime comrade-in-food, Chris Artis.

2. Historic Lombardi's photos provided by Gerry Lombardi.